The Exterminating Angel at the MET

- Scott Williamson

- Nov 4, 2017

- 7 min read

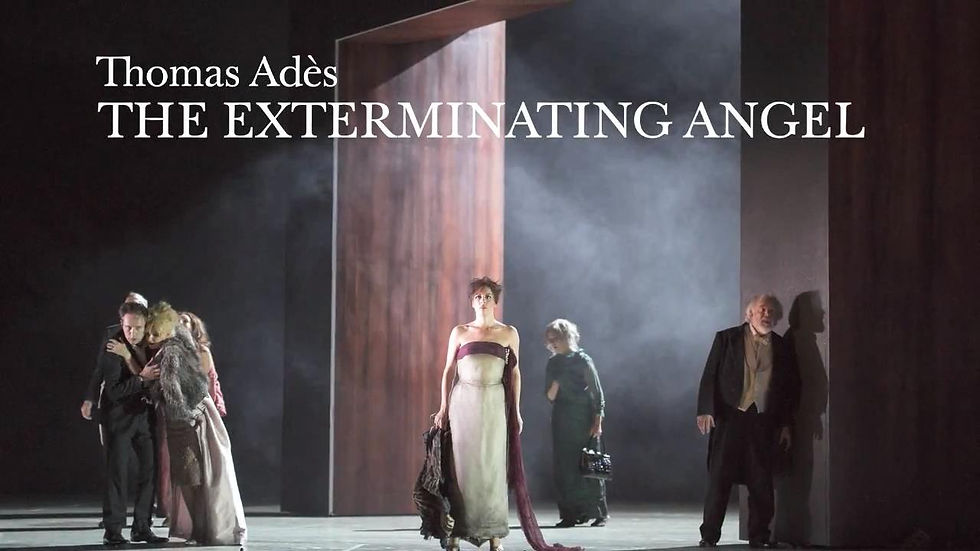

Thomas Adès | The Exterminating Angel | MET HD 11.18 | Notes and quotes...

__

I believe that music is a vehicle that can carry you from where you are to a different place. – TA

Musing on the The Exterminating Angel and it’s astonishing virtuosity – both in its uncompromising vocal and musical demands, and in the boldness of its creator’s imagination – the use of the ondes martenot (a prototypical “synthesizer” whose “swoopy” sounds resemble the fantasy and horror-film scores which called for a Theremin) – the onstage bells and sheep – the sheer audacity to attempt an opera on one of the strangest pillars of surrealism, a cornerstone film in a cornerstone era of film, itself created by an genre-crossing, tradition-defying, unpindownable genius like Buñuel –

Adès is like the Stravinsky of our day, and the Britten / Bernstein of his generation – an original and controversial, attention-deserving genius who is a triple-threat as a widely-performed composer, an accomplished and busy performer, and an internationally acclaimed conductor. (And like the above two B’s, Adès is a concert pianist, chamber musician and accompanist / collaborative artist).

And he’s been doing it since he was a teenager, championed by the likes of Rattle, Masur, Henze, and the classical musical “establishment” (whatever that still is…) Thus, like Britten, Korngold, Mendelssohn and Mozart, he's a prodigy who’s career has continued (at least into middle age) with notable achievements and accumulating successes…

One of his gifts, like Stravinsky, Bartok, or Berg (to name three of his “heroes”) is to assimilate previous styles, and like a Renaissance alchemist or magus, refine them in his own creative cauldron until the “pure gold’ or the “philosopher’s stone,” in the form of the “new work” (or opera, quartet, or song) emerges, distinct from what came before, as much a product of the creative artist and the creative “fire” of “inspiration…" (again, whatever that is!)

Like Birtwistle or Boulez, like Messiaen, or in homage to Couperin, the Viennese Waltz, or whatever influence he is absorbing and assimilating into what makes him “Adès,” (and not merely a pastiche composer), he continues a tradition by reinvigorating it. His voice is original, engaging and unfailingly energetic; it is music charged with electricity. His music is like an “action” painting; a wild, sometimes violent Picasso, an abstract-expressionist collage of counterpoint so dense it’s difficult to distinguish individual lines within the incredibly complex texture that only a genius could first imagine and then (with technique, vision, “inspiration,” persistence, strength and perseverance) help hold together…

From Alex Ross’s review of the original Salzburg world premiere of Exterminating Angel (New Yorker, August 22, 2016):

The British composer Thomas Adès is as compelling as any contemporary practitioner of his art because he is, first and foremost, a virtuoso of extremes. He is a refined technician, with a skilled performer’s reverence for tradition, yet he has no fear of unleashing brutal sounds on the edge of chaos. Although he makes liberal use of tonal harmony.. he subjects that material to shattering processes. He conjures both the vanished past and the ephemeral present; waltzes in a crumbling ballroom, pounding beats in a pop arena. [cf: Asyla’s “ecstasio” third movement, like a hallucinogenic 80’s or 90’s late-night rave at a club – the most original and striking evocation of contemporary pop music in a classical score since Bernstein, and truly sui generis in a major classical symphonic work…]

Ross continues: Like Alban Berg, the 20th c. master whom he most resembles, he pushes ambiguity to the point of explosive crisis. Concerning the composer’s vs. the filmmaker’s style, Adès is, however, more of an Expressionist than a Surrealist, and in his hands Buñuel’s cool, eerie scenario takes on a tragic volatility. So it’s operatic. Melodramatic. Over the top. It becomes the opera its subject has as its impetus. It reminds me of Tosca, and that’s a compliment to both composers.

Adès has favored cycles of intervals that expand and contract with organic logic…As in Berg’s 12-tone music, such operations yield a phantom tonality that never stays fixed. Yes, “phantom tonality,” that’s a perfect description of his post-modern, post-expressionist, post-abstract-expressionist idiom…

The Adès orchestra, meanwhile, rivals the Buñuel camera in imagistic power. The ondes martenot plays a pivotal role, serving to signal the nameless force that ensnares the guests. When Julio takes his final step, the instrument swoops to the bottom of its range – ‘as if swallowing the orchestra,’ the score says.

Also, the ondes martenot and its connection back to classic (=surrealist, cult, et al) film, also back to Messiaen and Les Six, also contemporaneous with his fellow Brit composer and ondes martenot virtuoso, Johnny Greenwood (from the alt-rock band, Radiohead… The link just above features the player for whom Adès wrote his demanding, pervasive part, Cynthia Millar. She is one of the only principal roles to have been featured at each of Angel's three premiere productions...)

That triumvirate of connections - Messiaen, Les Six, Radiohead - is telling for this particular younger cousin of Elgar and Holst, Walton & Tippett, Janacek & Kurtag… Like many a multi-talented, Renaissance-type polymath, Adès is a chameleon in the best sense – like Whitman, he “contains multitudes” – his palette is bold and many-colored, his range wide; his virtuosity prodigious as his ear and voice.

(Analogy: Take all of the composers mentioned thus far as spices in a blend for a soup unlike any you’ve encountered; it’s spicy and bold, interesting and “different”, and you can’t place what this “cuisine” is, which has either awakened or assaulted your taste-buds. It is in no way bland, plain, processed or predictable… You at least hand it to the chef(s) for how bold, original and at least well-crafted their entry was in this particular field of competition….)

Ross: Buñuel resisted efforts to articulate the meaning of The Exterminating Angel. The demand for explanations, he once complained, was itself a symptom of a bourgeois mentality. Adés has been more forthcoming… He defines the destroying angel as ‘an absence of will, of purpose,’ and says, “The feeling that the door is open but we don’t go through it is with us all the time.” An instant of inaction brings about ‘the complete breakdown of society… and ultimately the end of the world.’ It’s a lesson worth pondering at an ominous historical moment.

__

more Adès notes (from Oct. 2017 Opera News, by William R. Braun):

Adès’s mother was ‘the’ expert on Dalí and photo-montage Surrealism in general. She did the biggest exhibition on Dalí there’s ever been in Venice. She knew him. I used to watch Buñuel films when I was thirteen, fourteen… Surrealism is something that was literally in the house all the time… that sort of fantasy, played very dry, always appealed to me… It was an odd taste for a fourteen-year-old.

The film, of course, is quite dry, quite understated – that’s part of its brilliance…. I needed to find an equivalent for the fantastical moments in the film… I needed… to make a poetic moment. I found I wanted to have a further dimension… And it ended up having this Jewish element… I have two Jewish texts. The Ladino one [Spanish-Portuguese dialect from 15th c. Mediterranean diaspora] is just a folk song, and I make variations…Then there’s the song that Leticia [the Tosca character; she’s an opera singer playing herself at a dinner party after a performance of Lucia…] sings at the end…It [the poem by Yehuda Halevi] was written in Spain in the 1100’s. It’s about a yearning for Jerusalem, and there are so many images in it that are close to Buñuel… a very powerful expression of yearning for home. I just wanted her to have that mystical vision, almost of speaking in tongues.

He mentions John Tomlinson’s moment “with the Wagner tubas, it’s the whole collapse of the world at this moment. And John will articulate it…he brings out all of the pathos of the character… It was like something from Wotan’s farewell.” [Personal anecdote: I have fond, grateful, lucky-to-have-been-there memories of his Wotan in Bayreuth, 1996-97 under Levine; the reigning Wotan in the 90’s, he can be seen in Harry Kupfer’s “laser-light-show” production, also from Bayreuth, conducted by Barenboim. Tomlinson is also closely identified with the works of two other leading British composers of the 20th-21st centuries, Benjamin Britten and Harrison Birtwistle...]

Adès takes advantage of the poignancy in writing for a character playing a version of his now-aged self. It will be especially moving for Tomlinson fans, as he is one of the great ‘grey eminences’ (he could play Gandalf in LOTR: The Opera to Rule All Operas… I'm just sayin’… Somebody write it now...) A

Returning to the Opera News interview with the composer. Angel is a story with the circularity and seemingly endless paths of an Escher drawing, Adès uses a distinctive musical device. There’s a chord of 3 or 4 notes where one note at a time, but only one, continually slides downward.

The composer speaks more and more quickly about the excitement of the discovery. ‘If these little cells reveal themselves at some point as having a reality in the piece, suddenly look useful, I often find that, indeed, rather like a real seed, they unfold in all sorts of other possible ways… I used Wagner’s rule that you square it & cube it & you end up with all sorts of other proliferations.’

The “mazes and tunnels and trapdoors” and “endless sequences” in his music. See also: the major orchestral tone poem / one-movement symphony, Tevot, the Violin Concerto (Concentric Paths, whose movements are descriptive of its composer’s methods: I: Rings; II: Paths; III: Rounds), his first major symphonic essay, for Simon Rattle, the much-acclaimed Asyla (which plays on the multiple associations of its title, the plural of asylum), the piano concerto for moving image, In Seven Days, and the visionary orchestra tone poem (also with moving image), Polaris…

Paul Griffiths, in the “About the Music” note for the premiere recording of In Seven Days observes:

In Seven Days is a fractal composition, a work in which certain simple elements – as simple as the rising scale step… - are repeated again and again in contexts that are in a perpetual state of change thanks to the composer’s virtuoso control of rhythm and, especially, harmony, his twisted tonality emerging, totally fresh, from decades of popular music as well as from the classical tradition.

Almost any one of its seven would correspond to Rosemary Laing’s digital print greenwork (above, and referenced in a separate post / piece; and on view at the Taubman Museum…Laing and Adès have interesting points in common; similar procedures are at work: the manipulation of traditional materials, the playfulness and subversiveness, the bold use of color and the audacious juxtapositions…) Of the 2nd movement, Griffiths notes,

The separation of sea and sky, for instance, is imagined in what might be an infinite simultaneity of ascending and descending lines, perhaps suggesting Escher’s perpetual staircases.

Or the surrealist world of a Buñuel film. Or the reimagining of a fantastic Shakespeare hybrid-masterpiece like The Tempest (his 2nd opera, Angel’s next of kin, was seen at the MET in 2012).

__

Comments